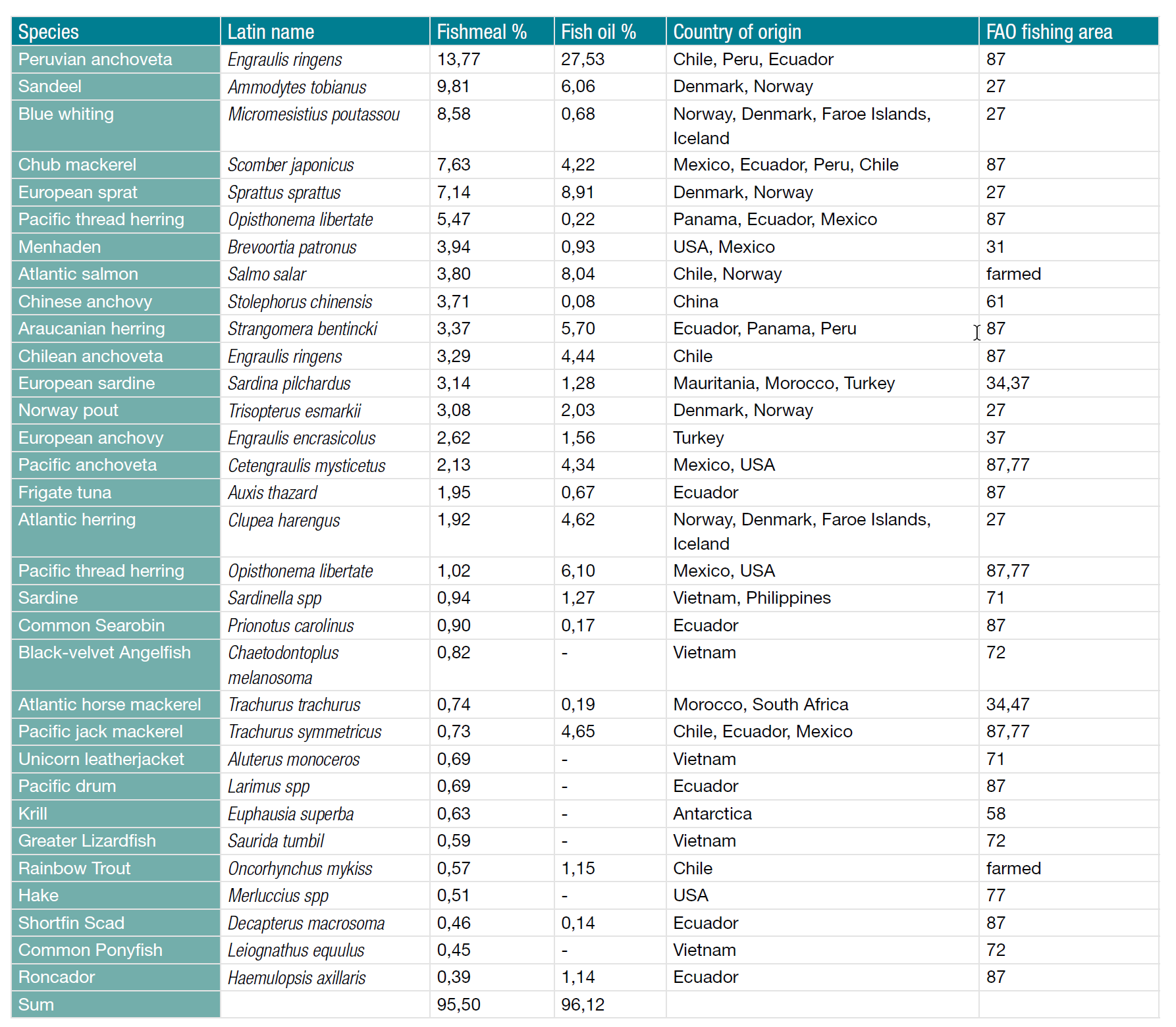

For more than a decade, Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP) has been working with leading feed companies like Nutreco/Skretting to track the status of key fisheries globally used in the production of marine ingredients (fish meal and fish oil), and support precompetitive collaboration to drive improvements where needed. Over that time, the overall sustainability status of these fisheries (as measured by FishSource) improved through 2017, but has since plateaued with some fisheries even slipping backwards.

For more than a decade, Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP) has been working with leading feed companies like Nutreco/Skretting to track the status of key fisheries globally used in the production of marine ingredients (fish meal and fish oil), and support precompetitive collaboration to drive improvements where needed. Over that time, the overall sustainability status of these fisheries (as measured by FishSource) improved through 2017, but has since plateaued with some fisheries even slipping backwards.

Over this same time, business and consumer awareness of and attention to the sustainability of marine ingredients has expanded dramatically. Where once little attention was paid the sources of marine (and other) ingredients used in aquaculture feed, there is now increasing interest in full ingredient transparency and life cycle analyses. While driven partly by a general growth of interest in seafood sustainability, this increased attention is also the result of growing understanding of the not only the environmental challenges in some of these fisheries, but the potential for significant social problems including labor abuse, food insecurity and displacement of small-scale fishers. Recently, some groups have been using these concerns to demand that companies switch from marine ingredients to alternative protein (eg insects, algae) in the name of sustainability (with the sole argument that they are not fish, which ignores potentially major sustainability tradeoffs). It must be noted that while aquaculture feed is the main use of marine ingredients, these same ingredients are used in a range of other products including pet food, nutraceuticals, cosmetics, baby formula and others.

With all this in mind, SFP welcomes the new responsible sourcing policy developed by Nutreco and Skretting. It represents an expanded commitment by the companies to improve their own practices, and acknowledges that companies must do better faster to deliver sustainability. It also specifically calls out a number of key challenges and opportunities facing the industry.

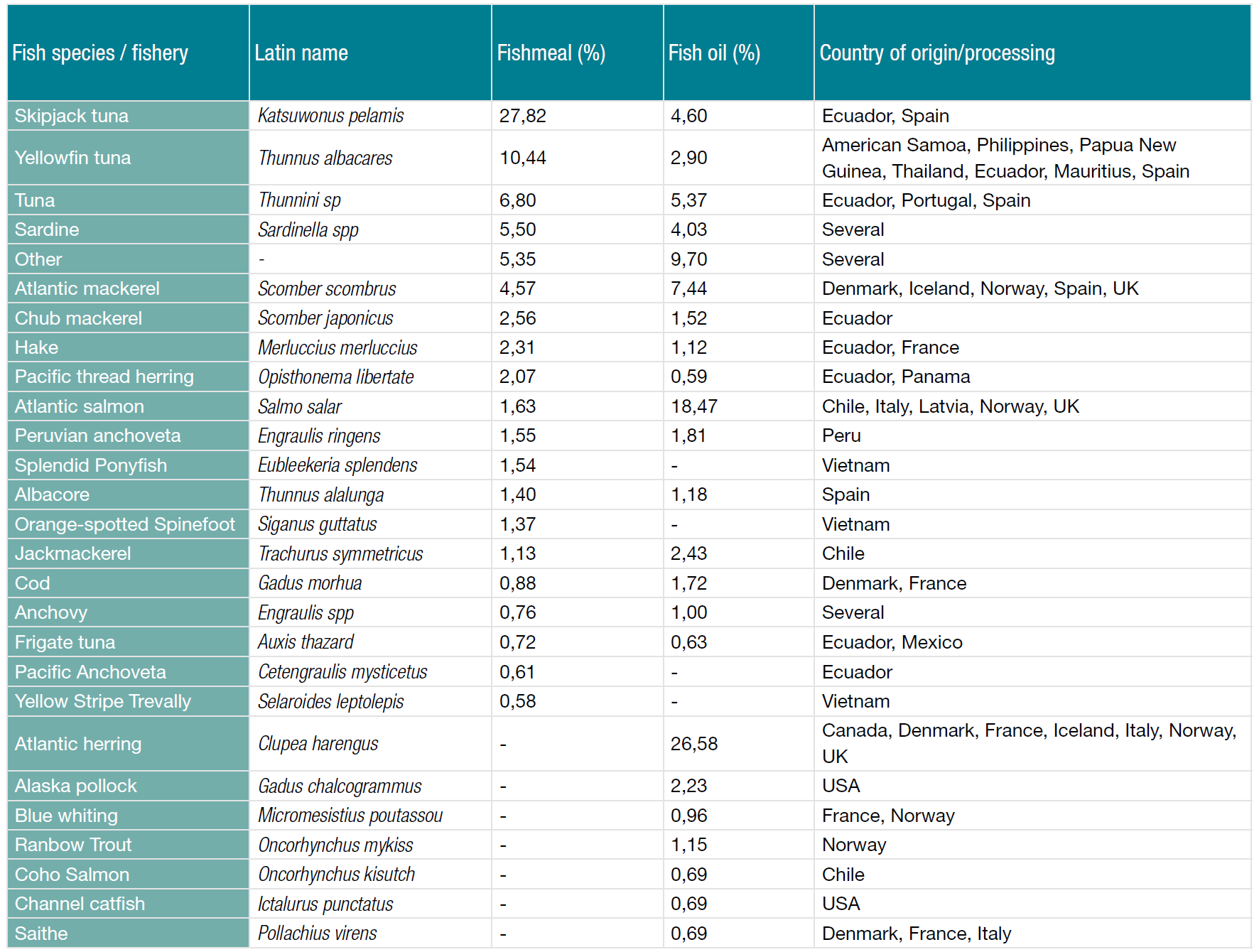

Transparency: Buyers of marine ingredients must work with the whole supply chain to improve sourcing and traceability of responsible ingredients, and public reporting through the Ocean Disclosure Project helps demonstrate this commitment.

Traders: Global trading companies are an integral part of the marine ingredients supply chain (as well as other ingredients used in aquaculture and pet feed). They buy and sell huge volumes yet are largely invisible, and can make or break sustainability and traceability efforts.

Multispecies fisheries can capture hundreds of species in a single net and may account for as much as half of fishmeal and oil produced globally. There is as yet little international consensus on what “good” management looks like in these fisheries, let alone any adequate certification criteria or scheme (although work is underway).

Forced Labor and Food Security are two significant risks. Companies must conduct due diligence to work with suppliers to eliminate labor abuses, and must be committed to not source from fisheries that undermine local food security.

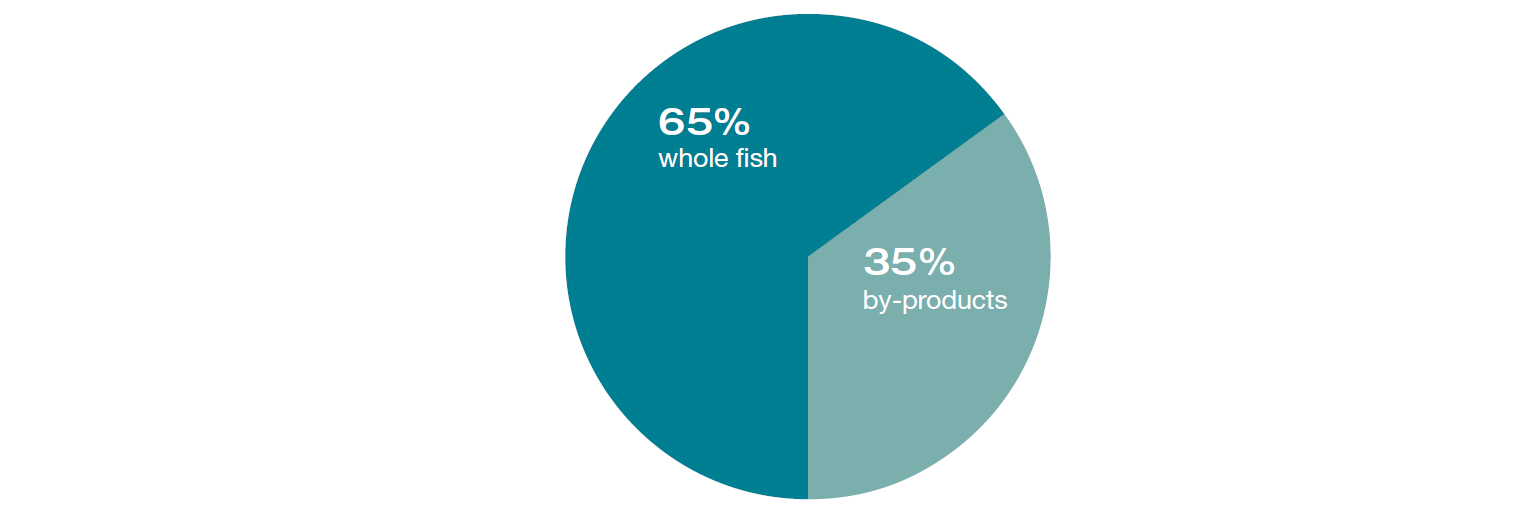

Increased use of byproducts is a good approach to increase efficiency, decrease waste, avoid food security issues and potentially improve local seafood processing capacity.

Key to addressing these and other challenges is the understanding that one company cannot do it alone. Which is why it is so important the Nutreco/Skrettying have participated in numerous precompetitive collaborations and are early members of the Global Roundtable on marine ingredients. SFP looks forward to working with Skretting to meet the commitments contained in their new policy and help address these global challenges.

Dave Martin, Program Director, Sustainable Fisheries Partnership

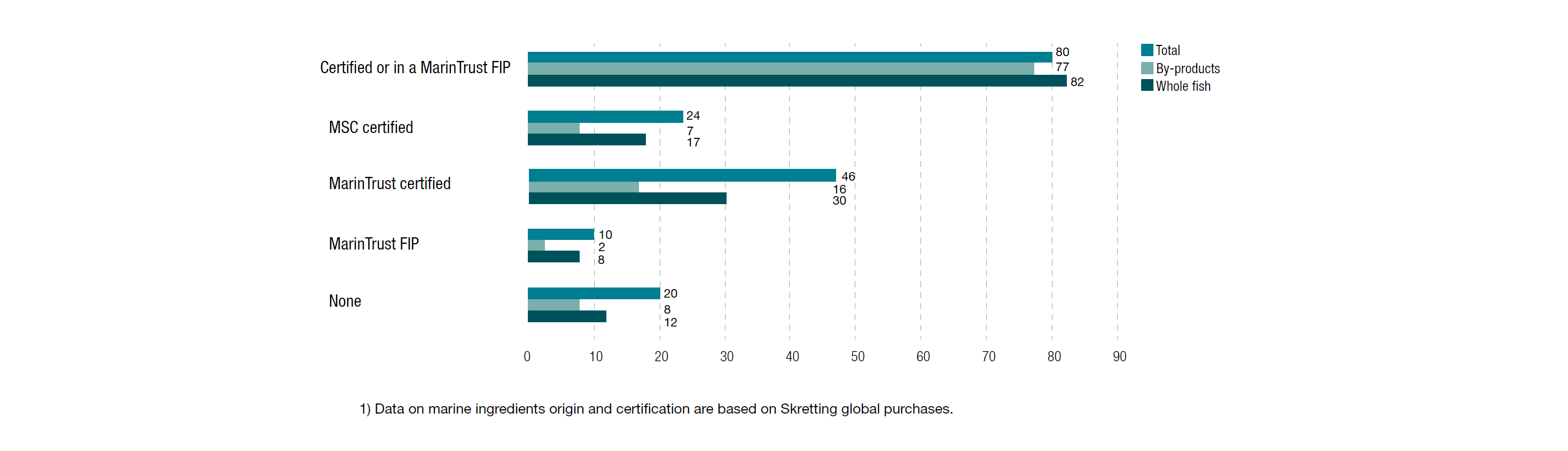

To protect the ocean and ensure that fish stocks intended for direct or indirect human consumption are caught within clearly defined, sustainable limits, in Q1 2022 Nutreco and Skretting published a new responsible sourcing policy which serves as a practical guide to decide on the type of marine ingredients that can be sourced for our global operations.

To protect the ocean and ensure that fish stocks intended for direct or indirect human consumption are caught within clearly defined, sustainable limits, in Q1 2022 Nutreco and Skretting published a new responsible sourcing policy which serves as a practical guide to decide on the type of marine ingredients that can be sourced for our global operations. For more than a decade, Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP) has been working with leading feed companies like Nutreco/Skretting to track the status of key fisheries globally used in the production of marine ingredients (fish meal and fish oil), and support precompetitive collaboration to drive improvements where needed. Over that time, the overall sustainability status of these fisheries (as measured by FishSource) improved through 2017, but has since plateaued with some fisheries even slipping backwards.

For more than a decade, Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP) has been working with leading feed companies like Nutreco/Skretting to track the status of key fisheries globally used in the production of marine ingredients (fish meal and fish oil), and support precompetitive collaboration to drive improvements where needed. Over that time, the overall sustainability status of these fisheries (as measured by FishSource) improved through 2017, but has since plateaued with some fisheries even slipping backwards. Certification offers a credible way of recognising and rewarding responsible practices. The ASC standards assess whether aquaculture farms are operating responsibly and the consumer facing logo is proof of achievement in a market leading programme for the production of responsibly farmed seafood. However, to make aquaculture more sustainable, it is essential to address feed which can make up as much as four fifths of aquaculture carbon emissions.

Certification offers a credible way of recognising and rewarding responsible practices. The ASC standards assess whether aquaculture farms are operating responsibly and the consumer facing logo is proof of achievement in a market leading programme for the production of responsibly farmed seafood. However, to make aquaculture more sustainable, it is essential to address feed which can make up as much as four fifths of aquaculture carbon emissions. The Small Pelagics FIP (Fishery Improvement Project) in Mauritania was initiated in 2017 by OLVEA Fish Oils and several of their suppliers, but has since then extended to include a wider subset of stakeholders across the entire sector, including Skretting from 2021, in Mauritania and beyond.

The Small Pelagics FIP (Fishery Improvement Project) in Mauritania was initiated in 2017 by OLVEA Fish Oils and several of their suppliers, but has since then extended to include a wider subset of stakeholders across the entire sector, including Skretting from 2021, in Mauritania and beyond. Skretting Italy’s CarbonBalance® was shortlisted as a finalist in the Product Innovation of the Year category of the prestigious edie Sustainability Leaders Awards 2022. This is a fantastic achievement in a year where edie receive its highest number of entries ever, and an important recognition of the work we’re doing across Nutreco to achieve our purpose of Feeding the Future.

Skretting Italy’s CarbonBalance® was shortlisted as a finalist in the Product Innovation of the Year category of the prestigious edie Sustainability Leaders Awards 2022. This is a fantastic achievement in a year where edie receive its highest number of entries ever, and an important recognition of the work we’re doing across Nutreco to achieve our purpose of Feeding the Future.